Becoming a Top 50 country on the Global Innovation Index

A country's innovation ecosystem can be hacked for performance--but not without ambition, preparation and hard work.

Can you guess which country is one of the fastest risers in the World Intellectual Property Organization’s (WIPO) Global Innovation Index? First, a measure of how rapid the rise of this country really is. A decade ago, back in 2014, it was 134th out of 143 countries of the world. Five years later, in 2019, it was 105th out of 129 countries

This year, it has come in at 91st out of 133 countries.

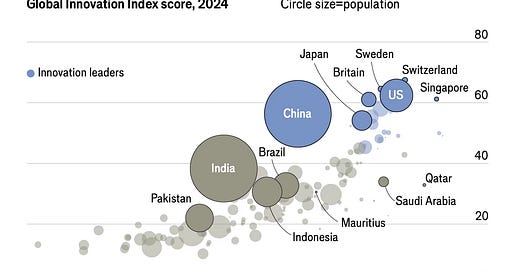

This rapid riser in the Global Innovation Index rankings is none other than Pakistan. It has risen 44 places in one decade. The Economist mentions Pakistan as one of countries that have most rapidly accelerated up the rankings, along with Indonesia, Mauritius, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Brazil. Ordinarily, Pakistanis are used to watching Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Brazil lap them. Qatar is all kinds of powerful—for all sizes, but especially its tininess. Saudi Arabia, Brazil and Indonesia are the varying toasts of the G20, with Brazil presiding and hosting in 2020, Saudi Arabia in 2022 and Indonesia in 2023. I got nothing on Mauritania, but to the naked eye, Pakistan is the real outlier in this list of fast climbers on ANY positive measure of global standing. That this is coming on the back of an almost, now three-year long polycrisis that burst through the dams in March 2022 is even more perplexing, exciting.

At this rate, by 2034, Pakistan should be in the global top 50. But getting from 134th to 91st may prove to be a lot easier than getting from 91st to 47th. The reason is simple. Indices like the GII are imperfect, but they are’t stupid. Measuring a country’s innovation ecosystem is tricky, but there are some basics that are largely agreed upon.

What constitutes the GII ranking

The 2024 Global Innovation Index splits its metrics evenly across two factors, innovation inputs and innovation outputs, and seven pillars (below). Across these seven pillars, there are a total of 78 indicators. These fall into one of three categories:

quantitative / objective / hard data (63 indicators),

composite indicators / index data (10 indicators), and

survey / qualitative / subjective / soft data (5 indicators).

The innovation input sub index measures the quality of structural, policy and financial input goes into innovation in a given country through five metrics, namely:

Institutions

Human capital and research

Infrastructure

Market sophistication

Business sophistication

The innovation output sub index then measures the quality of innovation that a given country is producing through two metrics:

Knowledge and technology outputs

Creative outputs

Can you guess which metrics are driving Pakistan’s rapid rise?

Hint: it is not the government's actions that is causing this sharp and sustained improvement in Pakistan's innovation ranking.

What is fueling Pakistan’s rise?

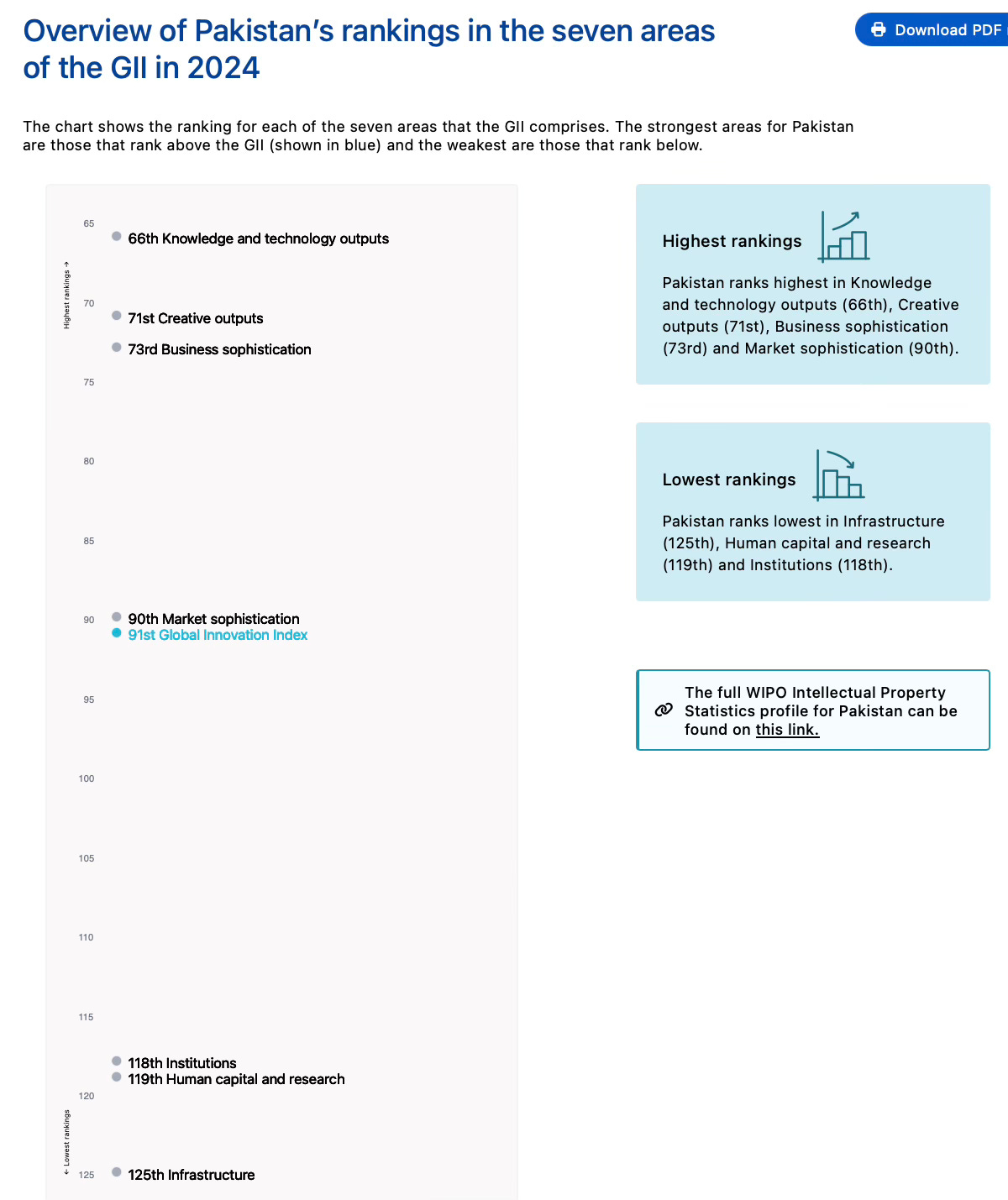

Pakistan’s performance, by pillar, is illuminating. Pakistan is doing outstandingly better than it should be (given the size of its economy) on the innovation outputs, coming in at 66th out of 129 countries for knowledge and technology outputs, and 71st out of 129 countries for creative outputs. Conversely, and unsurprisingly, Pakistan is doing poorly in terms of innovation inputs—with its investment in innovation infrastructure being almost the bottom of the rankings, and its human capital and research and institutions not too far above the bottom.

Think about it a little bit, and the oft-lionized indomitable spirit of ordinary Pakistanis is even more impressive. Those knowledge and tech outputs, and that creativity that Pakistanis are generating, are being squeezed from among the weakest and driest innovation base in the world. In other words, maybe no country’s people and private sector deliver more bang for the buck (in terms of return on investment in innovation) than Pakistan’s. The GII clearly states this too, if perhaps a little less effusively: "Pakistan produces more innovation outputs relative to its level of innovation investments". (India’s performance in this regard is even more impressive—but that train choo-choos everywhere, all the time—more on that in a separate post).

The reason that the innovation outputs are able to pull up Pakistan’s score so rapidly has to do with the outsized influence that the output side of the equation is given in the GII. The five innovation input pillars make up half the index, the two innovation output pillars make up the other half.

Getting into the Top 50

Of the seven pillars of the Global Innovation Index, the three that Pakistan is overperforming on (knowledge and technology outputs, creative outputs and business sophistication) are the ones being driven by individuals and firms, mostly in the private sector.

The ones that government is responsible for: market sophistication, institutions, human capital and research and infrastructure are the four pillars that are dragging down the national performance--holding back the individual and collective brilliance of Pakistanis.

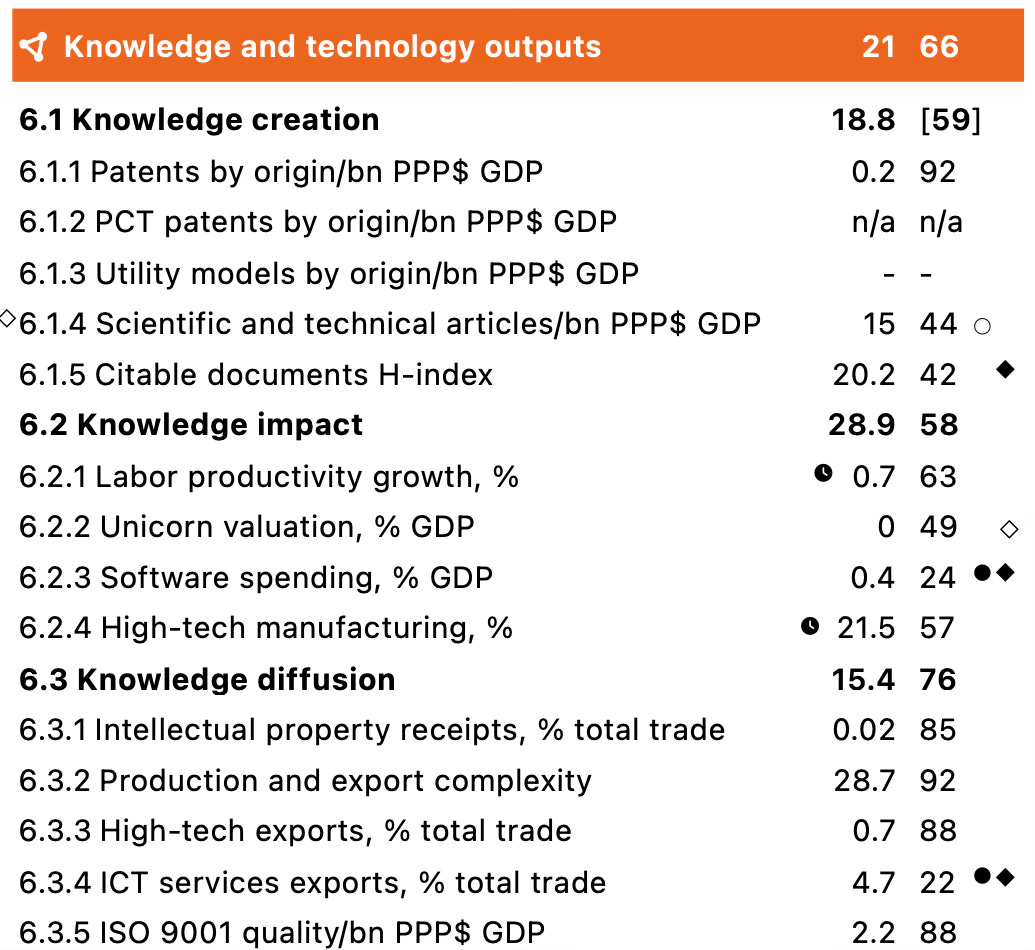

In the next decade, two really big challenges will face champions of innovation in Pakistan. The first is how to continue to drive high performance on the indicators that Pakistan is already doing well on (and even better—how to make that high performance more meaningful by investing more robustly in quality of outputs). The second is to improve performance on the indicators that Pakistan is not doing so well on. In both cases, the next evolution of improvement will require extraordinary movement in the right direction. Let’s take the example of the knowledge and technology outputs—the top performing pillar for Pakistan.

Now one simple way to think about moving into the top 50 globally is to look at the ranks within this pillar and think about where there is genuine room for improvement beyond 2024. Pakistan is already, by rank, in the global top 50 for “scientific and technical articles”, “citable documents H-index”, “unicorn valuation”, “software spending”, and “ICT services exports”.

Let us set aside the issue of whether there should be concern in terms of the robustness of these metrics and whether the data reflects reality. The more pressing reality is that to push through further, Pakistan’s real opportunity is to focus on where it is really behind the curve. In this specific pillar, it is clear that Pakistan has a long way to go on its rank for “patents by origin”, “intellectual property receipts”, “production and export complexity”, “high tech exports” and “ISO 9001 quality”. Now take a minute to let this really sink in. Here are the indicators where there is acrea of room for improvement in the knowledge and technology outputs pillar, in list format:

“patents by origin”,

“intellectual property receipts”,

“production and export complexity”,

“high tech exports” and

“ISO 9001 quality”

You see the trouble here? These are not indicators that can or will move easily. The ISO 9001 indicator and the patents by origin (maybe) can be projectised and improved rapidly with perhaps the least structural change—but the rest of these indicators are really complex. They require serious economic transformation. They require a fundamental shift away from the cheap, accounting tricks management of the Pakistani ecosystem to a highly ambitious, visionary view of Pakistani talent, and how to put it to work.

Any major change in these cannot come about without significant changes to the innovation inputs. And that’s full circle—the almost ubiquitous and inescapable reality that no matter the issue, and no matter the topline of good news today, the fundamentals of Pakistan’s future are hinged on a major investment in the quality of life that the country wants to give to the least privileged Pakistani child.

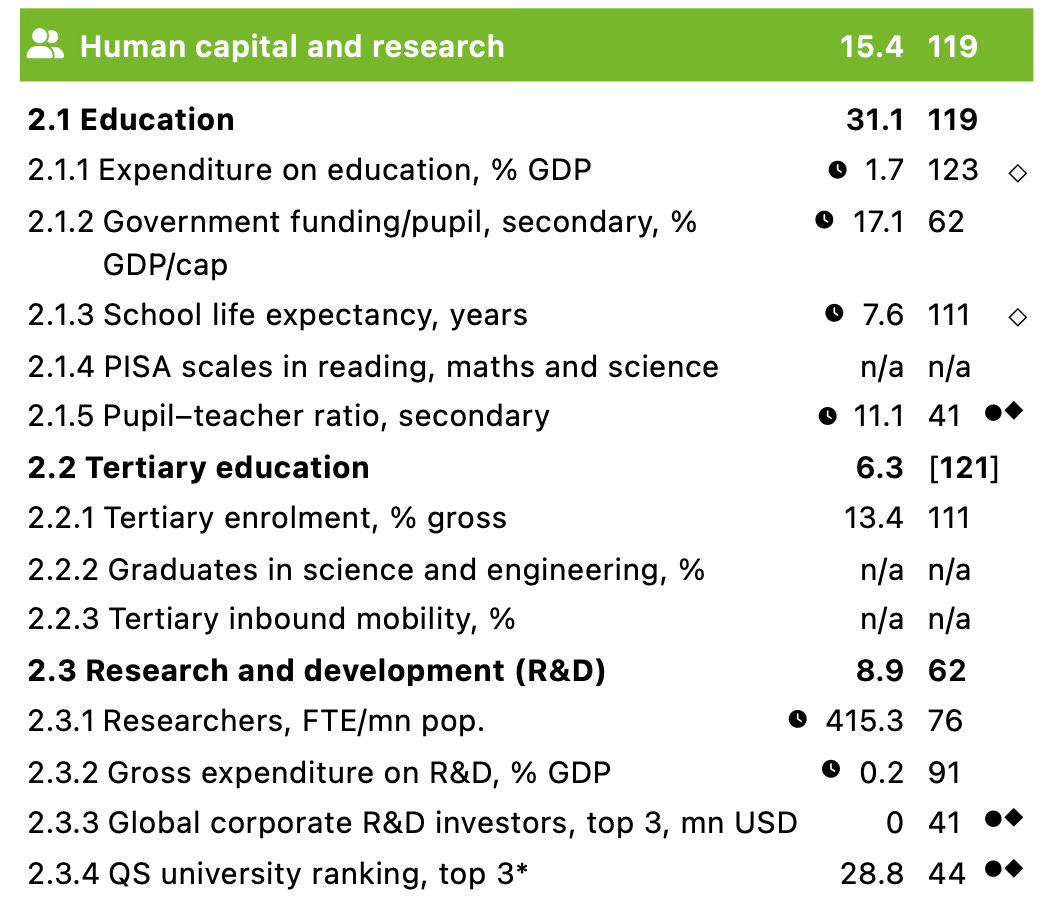

Here’s what that looks like in the 2024 GII index:

The issue here is not just that there is a poor human capital base from which Pakistan is working. The issue is also that of all the pillars, this is the one with the most outdated data—this being a function of a data regime in Islamabad that has little to no interest in reporting these statistics accurately or in a manner that is timely. Why? In part, because funding of human capital decisions are not informed by performance in building human capital. In part, because when there is an economic crisis (as there has been for the last three years), the first cuts are to university and school budgets—not the salaries of permanently tenured teachers with zero accountability—but rather to the expansion of net capacity, and investments in advanced capability (such as the use of technology to measure and empower students).

The results are clear to see. A country that is 44th in the world in the innovation indicator titled “QS university ranking” is also 123rd in the world in “expenditure on education”, and 111th in the world in “school life expectancy”, and “tertiary enrollment”.

Another way to think about this, a simpler way, is to understand that Pakistan essentially is beating itself in the global innovation index. It is clearly capable of delivering global top 50 level performance in several indicators (in both INNOVATION inputs and INNOVATION outputs)—but for indicators that are well within its control (spend more money, ensure more kids have more opportunity), Pakistan is leaving money on the table.

Fixing this is not rocket science. There are only 78 indicators. Each one of them needs to be pursued with relentless dedication.

A few indicators will be manageable for SIFC, or even ministries and departments—maybe even through simple notifications and a modest modicum of follow up. Other indicators will require dedicated teams from within the relevant provincial and federal organizations—this will be harder, given that no secretary or director ever seems to be able to complete the three year tenure that was the basis for the existing machine bureaucracy model that governs Pakistani administrative machinery. Most indicators will require coherent, collective, sustained team work, across multiple kinds of government and private bodies, and through different kinds of leaderships. Each indicator will require an ownership structure that protects progress against that indicator from a change in whoever is the chairperson of the HEC, or whoever is the secretary school education, or whoever is the joint secretary IT services, or whoever is the chairperson of the board of investment.

The good news is that Pakistan has rapidly risen over the last decade—through terrorism, war, conflict, natural calamities, man made crises, political collapse and economic dysfunction. If Pakistan has been able to rise from 134th to 91st in just one decade with almost no concerted or coherent effort at improving its standing on the Global Innovation Index—just imagine what Pakistanis might be able to accomplish with just a little bit of coming together and deciding to get better. Together.

Bismillah.

Hi Mosharraf,

This is an interesting and informative read.

The 3 out of 5 Innovation inputs are performing the most poorly with market sophistication fairly performing well in comparison to bottom 3.

I understand that most of the indicators of sub-indexes can be improved just through an action plan that doesn't require much effort but coherence between various institutions and consistent follow ups however this gives rise to two notable questions:

1. In your opinion, should government focus on better performing indicators as a strategy or start acting up on the worst performing ones?

2. On a bigger scale, what is the urgency of improving on input sub-indexes where cross-institutional effort is required where we understand that every institution has their own priority to take action on?