Indonesia in 1998 (and now)...

Is it just GDP growth or higher exports? Or is there more to it?

By June 2022, it was clear that Pakistan was in the midst of a profound crisis—triggered by the political mobilization that Imran Khan was able to generate after he was removed from office, but anchored in a broken economic model and a political compact that had been dismantled steadily, piece by piece, ever since it was reached in 2008. For over a year now, one of my primary preoccupations has been to try to understand how countries emerge from catastrophic circumstances—successfully.

There are two aspects of change in Indonesia in 1998 that are really fascinating. First, how the politics of the country played out, and how Indonesian generals evolved and melded into mainstream politics. Second, how the economy evolved, grew and transformed after 1998.

To do this with any sense of purpose as it relates to Pakistan required me to begin with some key conditions or filters—a large population size, a dominant military, complex geopolitical challenges, and perhaps as important as any, an overwhelmingly Muslim population. No matter how we slice it, this leads to two primary isomorphs (I use this term very deliberately, but for now, ignore how awkward and unnecessary a word it is). The first isomorph (or exemplar or comparator) and the one that is more relatable because of that country’s incredible soft power, is Turkey. The second isomorph, and the one that fits more readily, is Indonesia.

I wrote about Indonesia in 1998 here, and this article became a reference point for a number of serious conversations—both ones that I started myself and ones that have been taking place over the course of Pakistan’s enormous and unprecedented current “polycrisis” (thanks Adam Tooze!)

Too often since that article was published however, I find my knowledge about Indonesia wanting. Specifically, I find that the setting of an isomorph like Indonesia is problematic because whilst it is easy, in the aggregate, to identify things that we can point to that make Indonesia in 1998 very similar to Pakistan in 2022, or 2023 (or I am afraid, 2024, 2025 and beyond), it might be more important to try to identify the things that made them different.

There are two aspects of what happened after 1998, or as a result of the changes in 1998 that are really fascinating from a distance. First, how the politics of the country played out after Suharto and BJ Habibie, and especially how Indonesian generals evolved and melded into mainstream politics (the roles played by Lt Gen Agus Widjojo, Gen Wiranto and Lt Gen Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono—who was elected president of Indonesia six years after the 1998 crisis—merit a lot deeper interest than the kind of drive-by analysis outsiders can muster. Second, how the economy evolved, grew and transformed after 1998.

Let’s start with this second, economic dimension. One of the explanations for Indonesia’s dramatic transformation over the last quarter century that I am often given is that Indonesia enjoys a great endowment of natural resources. The implication here being that Pakistan can’t possibly be expected to change so swiftly and readily as Indonesia did—because, boo hoo, it lacks a similar endowment.

So I dug around to try to figure out how true this may be. And there is some interesting things that pop out of the data… but before we get to it, here is the overarching context for the Indonesia in 1998 isomorph for Pakistan—it is the intimacy of the start of these wormlines at the beginning of this version of our story in 1998…

As this story of a vast gulf in the sizes of the two economies opens up, so too does the vast gulf in exports…

The easy whine is to attribute this vast gap in the ability of Indonesia to generate valuable foreign exchange for its economy to the country’s substantial natural resource advantage. But when we explore how Indonesia’s exports have evolved in the last quarter century, and juxtapose this with what has happened to the exports profile of Pakistan, some interesting things emerge.

Thanks to the amazing work done by the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) folks, we can see the exports of a country broken down by the harmonized commodity description and coding systems (HS). This gives us a very clear picture of the diversity of a country’s exports and the product differentiation within this exports profile.

In 1998 this was the breakdown of exports from Pakistan…

It isn’t hard to see that the lion’s share—easily more than 70% of Pakistani exports in 1998 were related to, derived from, or directly of cotton, or cotton-adjacent products. by 2021, nearly a quarter century later, Pakistani exports were divvied up as depicted below…

It is a fun exercise to go through the differences and similarities between Pakistani exports over a full generation (by any stretch of the imagination). It is also important to remember: 1998 saw roughly $10 billion in exports whilst 2021 saw just a shade under $40 billion worth. At its core however, the enduring take away from the juxtaposition of the two image is that one peculiar sector (cotton and cotton-adjacent) has maintained its dominance in the spectrum of Pakistani exports.

Now let’s compare this with the isomorph that is Indonesia. Here is the exports profile of Indonesia in 1998—the year East Asia’s financial crisis caused a global economic slowdown, and President Suharto stepped down because the streets of Jakarta said, “no more”.

The first thing that pops out at me here is not the difference in quantum of exports—remember, in 1998, Indonesia had exports of about $57 billion (versus the shade under $10 billion that Pakistan exported back then). The first thing that pops out at me—and really, thanks to the visualization, it really *pops*—is how diverse the product mix of Indonesia’s exports already is in 1998. Even back then, Indonesia had like at least sixteen different categories that made up at least 1% of its exports (or roughly $500 million worth of exports each). No single category takes up more than about 22% of the total exports from Indonesia in 1998—and the top three categories combined (mineral fuels ~22%, clothing and cotton ~14%, and electronics and machinery ~12%) make up less than 50% of the total exports of Indonesia in 1998.

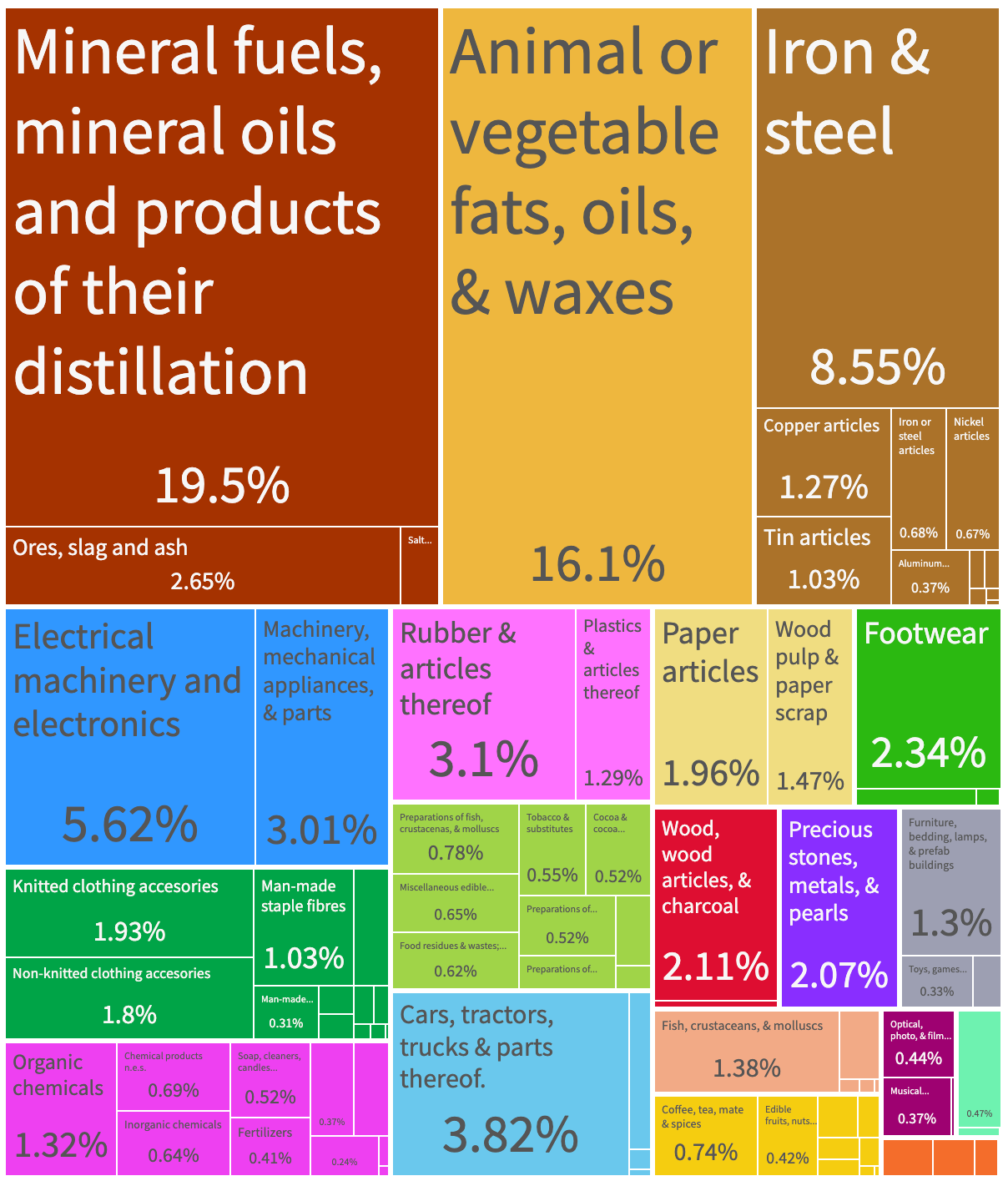

Now check out Indonesia, nearly a quarter century later in 2021…

The 2021 product mix is diverse, but not by that much more than it was in 1998. The more interesting thing that seems to have happened in Indonesia—that does not seem to have happened in Pakistan is the churn within the product mix. Mineral fuels maintain their top billing, and remarkably, their share stays almost exactly the same as it was in 1998. But of the top three, that is the only constant.

Two new categories take over completely from cotton and clothing, and electronics and machinery. In come metals at about 13% and animal or vegetable fats at about 16% of the total exports of Indonesia in 2021.

Let’s take each of these separately. At 16.1% vegetable or animal oils end up accounting for roughly $40 billion worth of exports in 2021. In 1998 animal or vegetable fats made up only 3.64% of Indonesia’s exports—or about $2 billion worth. So just in this single category, the quantum of change is 20x.

The metals category story isn’t much different. Iron and steel in 1998 made up 1.4% of Indonesia’s total exports—or about $752 million worth of exports. In 2021, iron and steel made up 8.55% of total exports—amounting to over $21 billion of Indonesia’s exports. Here the quantum of change is nearly 30x.

So are natural resources a real advantage for Indonesia and its economy. There is hardly any question that this is true. But it takes a certain degree of national capability and capacity to exploit natural resources in a manner that generates the kind of transformational advantage that Indonesia’s exports has generated for Indonesia.

In short, yes—Indonesia benefits from natural resources, but there is a lot more happening in Indonesia in 1998 and after, that helps propel the country from an inward-looking self-conscious and not very successful country less than a quarter century ago, to a lean, mean G-20 summit hosting, US-China competition resisting machine today.

Ironically, the roots of the diverse Indonesian economy may have been put in place not as a result of the 1998 crisis and the Suharto and Golkar regimes’ excesses—but due to their very efforts to normalize Indonesia and open it up for trade within the region and the wider world. And that brings us to the other fascinating aspect of the changes in Indonesia since 1998: the emergence of a post Golkar politics, the return of the TNI to the barracks, and the role of the warrior-philosophers generals of the late 1990s in curating, cultivating and governing this transition and transformation.

I’ll try to explore that in the next post.

Thanks for reading and please make sure you subscribe!