What Labour's UK 🇬🇧 aid budget cut means

The first Labour budget in 14 years says it won't even try to meet the 0.7% of GNI benchmark till 2030. UK aid used to be the poster child of how development should be done. How times change.

What just happened:

Understanding the UK aid “cut”

The (relatively) new Labour government in the UK just announced its first budget. Among the news items relevant to global audiences is what amounts to a significant cut in allocations for international assistance.

Bill Gates, among many others, has been critical of this reduction of British allocations for Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) or the money UK taxpayers spending on international aid. Essentially, the cash strapped UK government has decided it will continue to spend only 0.5% of its Gross National Income (GNI) on overseas assistance—as opposed to 0.7%. This is a huge hit—especially when we take into account the UK spending on asylum seekers being drawn from the wider envelope for ODA.

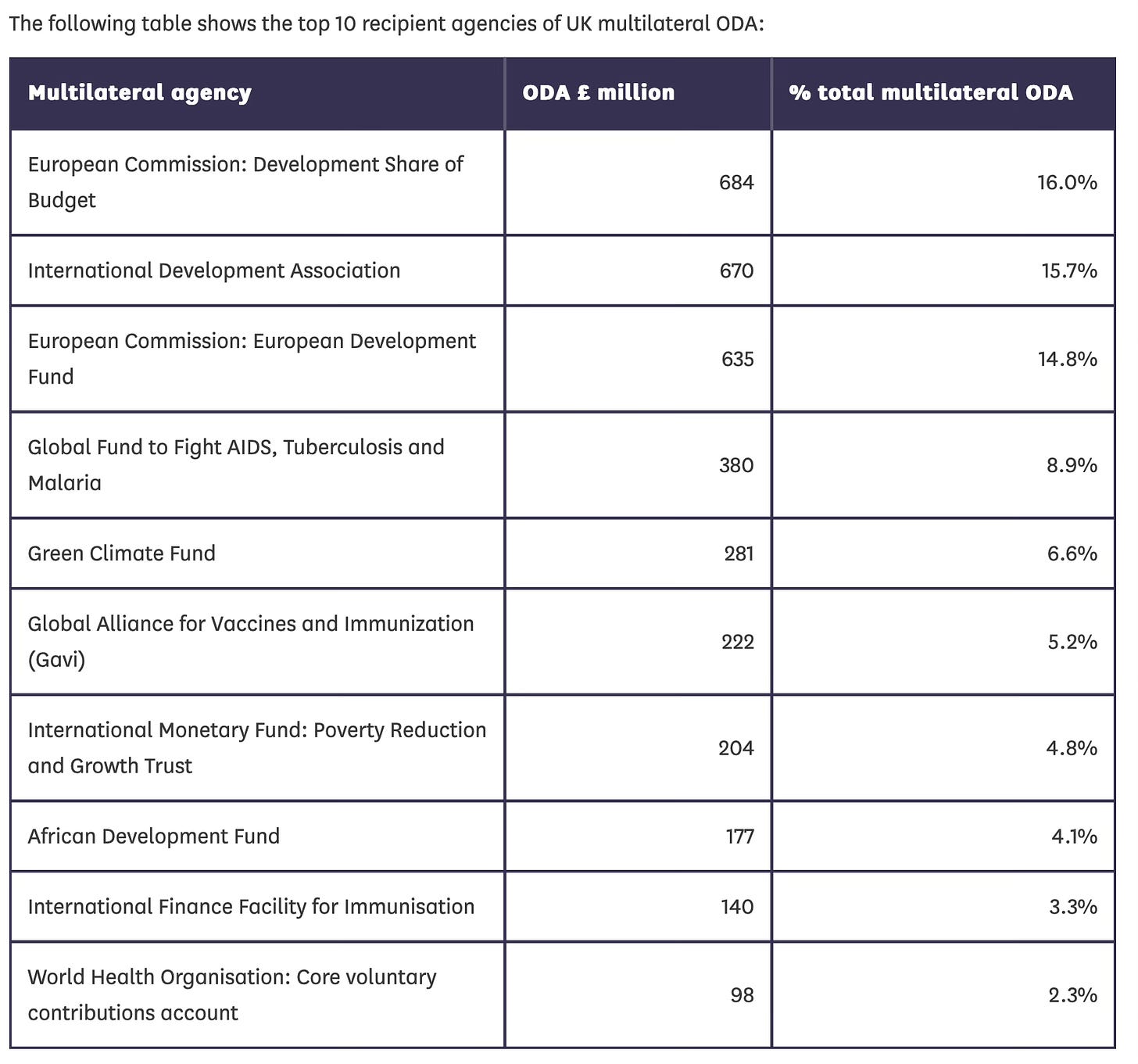

Gates is right. This is bad news, at a large and global scale, for a wide array of things that British taxpayers contribute to, including the fight to immunize all children against diseases like polio, the struggle to get all children into school and learning, climate adaptation in countries and communities that lack the resources and know how to establish homegrown adaptation tech, and resources to supplement even more severely cash strapped and debt crisis economies across the developing world. To get a sense of how central UK aid is to the global development landscape, consider just this data of UK contributions in 2021 to multilateral fora that work on some of the most vexing development challenges in the world.

This budget cycle in the UK is not new in terms of a debate about Great Britain’s commitment to development, and it’s not new in terms of Bill Gates weighing in. Back in 2017, Gates had encouraged the Brits to remain steadfast in its commitment to spending 0.7% of GNI on aid.

The reason the UK is so important in this debate is that it has enjoyed a stellar overall reputation, as well as unprecedented and outsized influence in the overarching discourse on international development and overseas assistance. How the UK government decides to do aid and assistance to developing countries has a really big impact on how development is thought about and done everywhere. Part of this influence is a product of the history of UK aid, and the legacy of something called DFID.

UK aid backstory: From ODA to DFID

British overseas development assistance (ODA) has enjoyed a remarkably resilient reputation as being deeper, more meaningful and more sensitive to the development needs and priorities of developing countries—especially since the United Kingdom first set up a separate ministry for international assistance in 1997. Some of the debates UK development aid ministers have engaged in on the global stage have helped shape entire eras of Western and industrialized nations’ approach to development assistance. When I was at DFID from 2004 to 2008, this role was played by DFID minister Hillary Benn, who basically put a gun to the head of the then World Bank president Paul Wolfowitz on the issue of how the World Bank would define and pursue the notion of aid conditionality. The principle DFID was espousing then was that development assistance should not be predicated on the kind of policies a recipient country was adopting or following—but rather on the outcomes that were being financed by development assistance. These debates on aid “conditionality” helped cement DFID’s reputation, at least among recipient countries and those that were worried about the creeping influence of neocons in international development, as a crucial interlocutor—and not merely a pool of resources. Insisting on the agency of recipient countries’ own systems was one of many things that made DFID a trusted partner for a spectrum of actors in development.

Prior to 1997, British development aid was spent through a government body called Overseas Development Administration or ODA—and this was often, though not always, a part of the British foreign ministry (known as FCO back then). The new development ministry set up by the Brits came to be known as DFID, or the Department for International Development. The dynamic between the foreign affairs function and the development assistance function had been an inflection point, not just in the UK but many OECD donor countries—especially those that were conscious of the burden of colonial rule. Many politicians and academics in the industrialized West saw the conflation of the aid function and the foreign policy function as being fundamentally in conflict with each other. The purists in this camp were simply appealing to our normative lens: rich nations should be underwriting improved outcomes in poor nations because it was the right thing to do—NOT because there were some diplomatic benefits to be accrued from doing that “right” thing. Others were adamant that the two functions (aid and foreign relations) should be kept separate because good “aid” or good development inputs (money and/or expertise and/or influence) required aid givers to prioritize the technical arcs of how development should work—rather than considerations contaminated by the narrow national interests of the aid givers. The colonial baggage of many aid giving, OECD countries meant that there was always an undercurrent of moral obligation that would creep into the development discourse—especially in the years right after the withdrawal of British, Dutch, French, Belgian and other colonial powers from their colonies in the 1940s, 1950’s, and through the 1960s. By the late 1980s, these imperative for aid were not just tied to problematic colonial baggage, and didn’t just signify relics of history. The integrity of the manner in which aid was being managed also came under the microscope.

In the UK, one major impetus for setting up a ministry independent of the foreign affairs function was the fallout from a legendary scandal known as the Pergau Dam fiasco. In 1988, British leaders used ODA to sweeten a defense deal—essentially exchanging a 236 million pound grant to build the Pergau Dam in Malaysia in exchange for a one billion pound arms procurement that Malaysia was going to run. The Pergau Dam story only broke years later (in 1993)—when the British official that headed ODA, and had tried his darnedest to stop it from happening, Tim Lankester—was identified by an audit report as having stood up and been counted. For months on end in the mid 1990s, the Pergau Dam fiasco animated British elites on the issue of international assistance.

When Labour won government in 1997, it set up DFID—but the impetus wasn’t solely Pergau or even the ideological conviction of DFID’s legendary founding minister, Clare Short (about whom Richard Dowden wrote in 2002, “Clare Short’s blunt talk in flat Brummie tones represented the honest worker, exploited and crushed by the moneyed classes. In a parallel universe, she might have become minister for class war and local co-operatives”. Short’s mythical status endures to date. The story-telling that comes naturally to development wallahs often centers “development” as the driver of international assistance or aid policy in wealthy countries.

In truth, the wider ideological environment and political “moment” are more central to how agendas on aid and assistance are shaped. In 1997, Britain was brimming with economic optimism about itself and the world—left had come to the centre, the right had withdrawn into a post John Major shell of itself. Globalization was the sexiest thing in the world. Eurocentrism was mainstream. Clare Short lead DFID for about six years, and only two of those years (2001 onward) were spent in the shadow of the post 9/11 development paradigm. Prior to September 11 and Britain’s inevitable entanglements (first in Afghanistan, and later in Iraq) DFID came to define very precisely the vision that Labour had mapped in its “Britain in the World” foreign policy manifesto for the 1997 election. The slow grinding erasure of the optimism of Blair’s “new” Labour was highlighted by Short’s resignation from his cabinet in 2003, shortly after the UK chose to join the US invasion of Iraq.

In 2020, when DFID was shut down and absorbed into the UK foreign ministry by Boris Johnson, an enduring wound was formed in the corpus of the traditional global development or international assistance discourse. The UK foreign ministry, which was traditionally known as the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), became FCDO—with the added D for development. This D continues to be seen by many as an imperfect fit, with many development wallahs clinging to a Clare Short world. In truth the merger, just like the original genesis of DFID, had a lot less to do with either the old FCO folks’ wanting to regain control of DFID budgets, or even with how much the wider Euroskepticism had engendered a reflexive resistance in the British public discourse for taxpayer money being shipped off to foreign countries. DFID perished because of the wider ideological environment and political “moment” that shaped Brexit and continues to shape British politics and society to date. Labour’s victory in 2024 is not a signal of a new epoch—it is a signal of the voter’s seeking a new midwife for the same things it previously thought Tories could deliver.

(nb. if you are interested, Mark Lowcock, one of my old boss’s bosses at DFID, and Ranil Dissanayake have written a great book about DFID).

Understanding the “0.7% of GNI”?

The Brits have been one of the few developed countries that had openly committed to (and for several years achieved) the spending of 0.7% of their national income on “official development assistance” (ODA), or foreign aid. The target of 0.7% of GNI is enshrined in UK law, most recently

This 0.7% of GNI (gross national income) figure for ODA was first agreed in 1970 at the United Nations, and since then, has become a core data point against which the OECD member countries, as well as the European Union had tended to measure themselves against. (nb. It is an entirely separate matter as to what the real or true purpose of ODA was for each country, or whether the manner in which these monies were spent was aligned with the needs or aspirations of the people of the countries for which they were allocated).

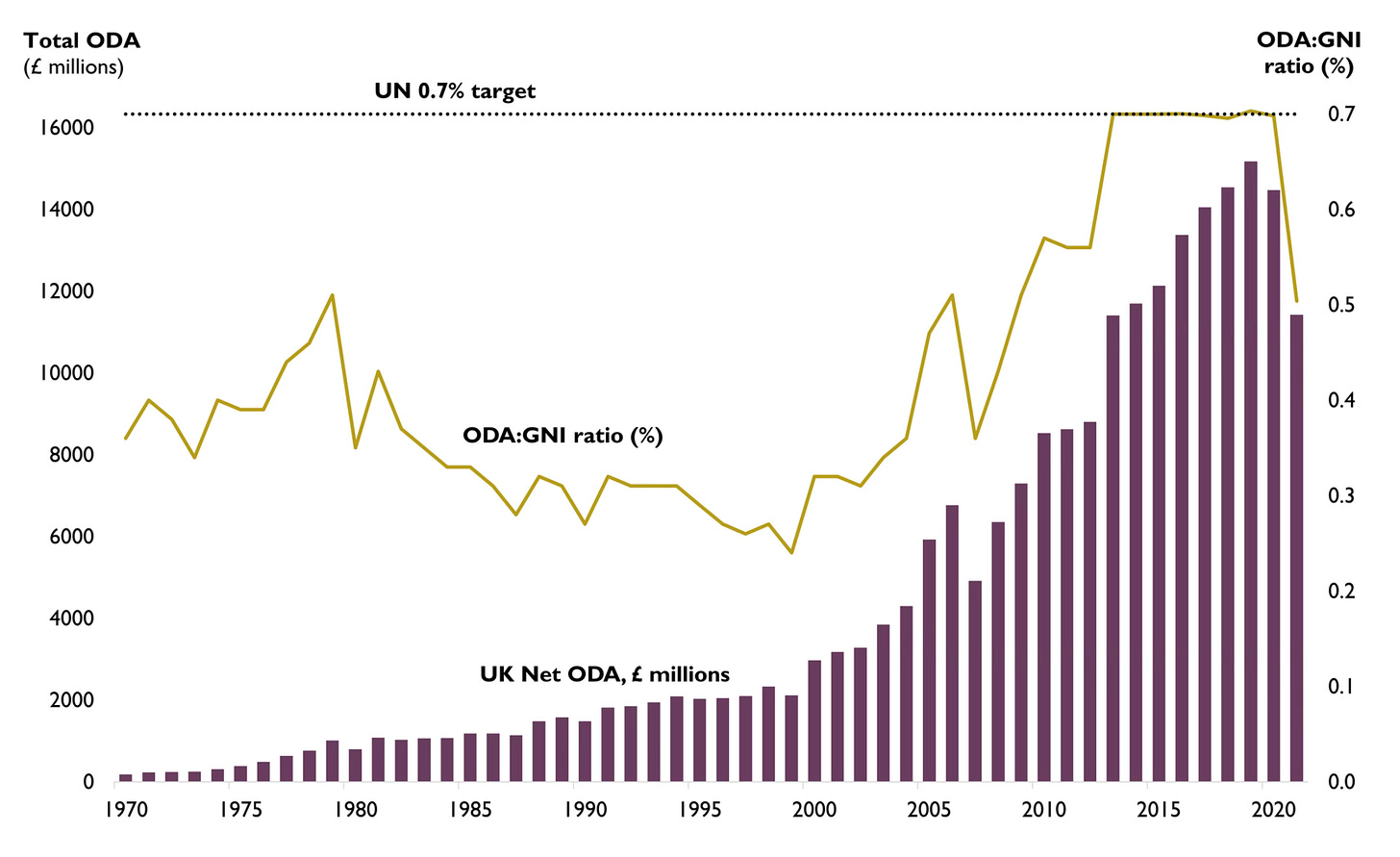

Here is UK ODA plotted both in terms of full cash and as a percentage of British national income.

From 2013 to 2020, the UK fulfilled its commitment of 0.7% of GNI for international aid. The narrative that the Tories never liked development and always wanted to cut funding for ODA, and get rid of DFID doesn’t really wash—given that the only years UK ever complied with 0.7% was during a sustained run of the Conservative Party’s dominance in British politics. 2020 was the year however that Covid-19 happened. It created the space for a wide array of fiscal prioritization conversations. The more extreme voices in the Boris Johnson cabinet found an opening. Even still, 0.7% remained a bit of a consistent theme.

In a parliamentary debate back in July 2020, after PM Johnson had announced the merger and prior to its actual execution on September 02, 2020, Foreign Secretary James Cleverly said:

“I remind all Members that the UK is one of the few countries in the world that spend 0.7% or more; we are the only country in the G7 that does so. That commitment is embedded in law, but we do not spend 0.7% because it is embedded in law—we spend 0.7% because it is the right thing to do.”

Even within the announcement of the DFID merger with FCO in June 2020 PM Johnson had stated Britain’s pride at being a 0.7% of GNI compliant country:

“The UK is the only G7 country to spend 0.7% of GNI on overseas development and the Government remains committed to this target, which is enshrined in law.”

The Labour Party’s 2024 manifesto explicitly commits to restoring the legally required British aid spending target:

“Labour is committed to restoring development spending at the level of 0.7 per cent of gross national income as soon as fiscal circumstances allow.”

In short, 0.7% of GNI, in addition to enjoying legal status, has also enjoyed the explicit bipartisan support of British political elites that very few issues or metrics do. And yet the Labour Party, that fountain of virtue from which DFID had sprouted twenty seven years earlier, has just announced that it will not only continue to short-change the British people of the satisfaction of spending 0.7% of their gross national income on aid—but that it will go further than the Tories in cutting back costs. That is essentially what the new UK budget is accused of doing to aid allocations from the UK.

The wider ideological environment and political “moment” in the UK is one of economic hardship and the exploitation of this hardship by populists across the spectrum of politics . The national discourse—fractured and bloodied by the horrifying riots this summer—had never really recovered from Brexit and has yet to begin healing from the violence and mayhem in the summer. Within this environment, UK ministers may appeal to NGO associations and development wallahs by reaffirming the UK commitment to 0.7%, but they will face no sanction from their voters for spending a lot less. In fact, Labour may yet be rewarded by voters for resisting the pressure from people like me (from the global South and professionally engaged in “development”) to pony up 0.7%.

Why? 👀 ⬇️

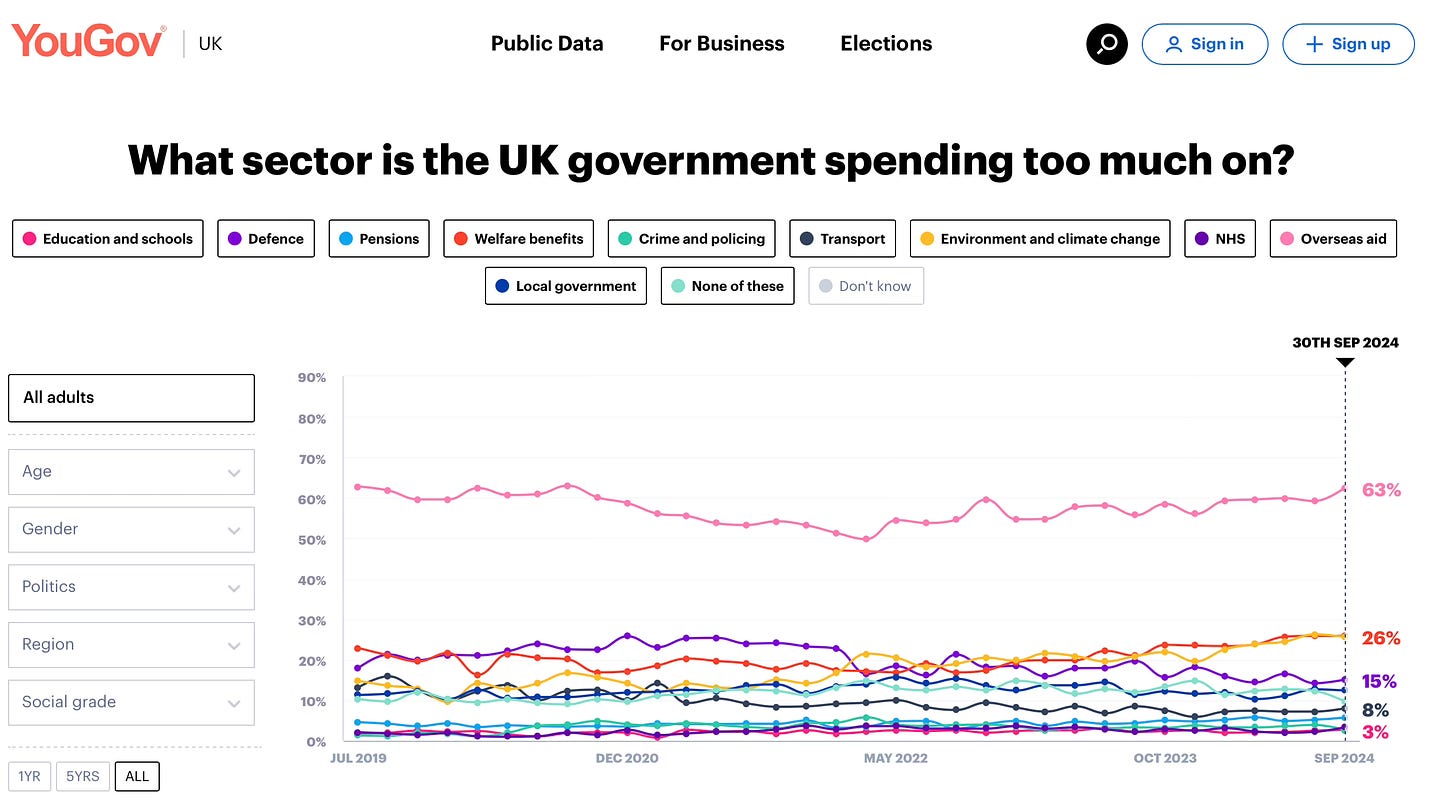

There may be hand wringing and ambiguity at Oxford Union or in the lecture halls at LSE and SOAS, but on Main Street in Little and Great Britain alike, there is zero confusion. Of all the things that the British people believe too much money is spent on, overseas aid is comprehensively lapping the field. Consistently. Pollsters are increasingly facing skepticism because of how frequently wrong they are. But this seems to be one that would be hard to get wrong.

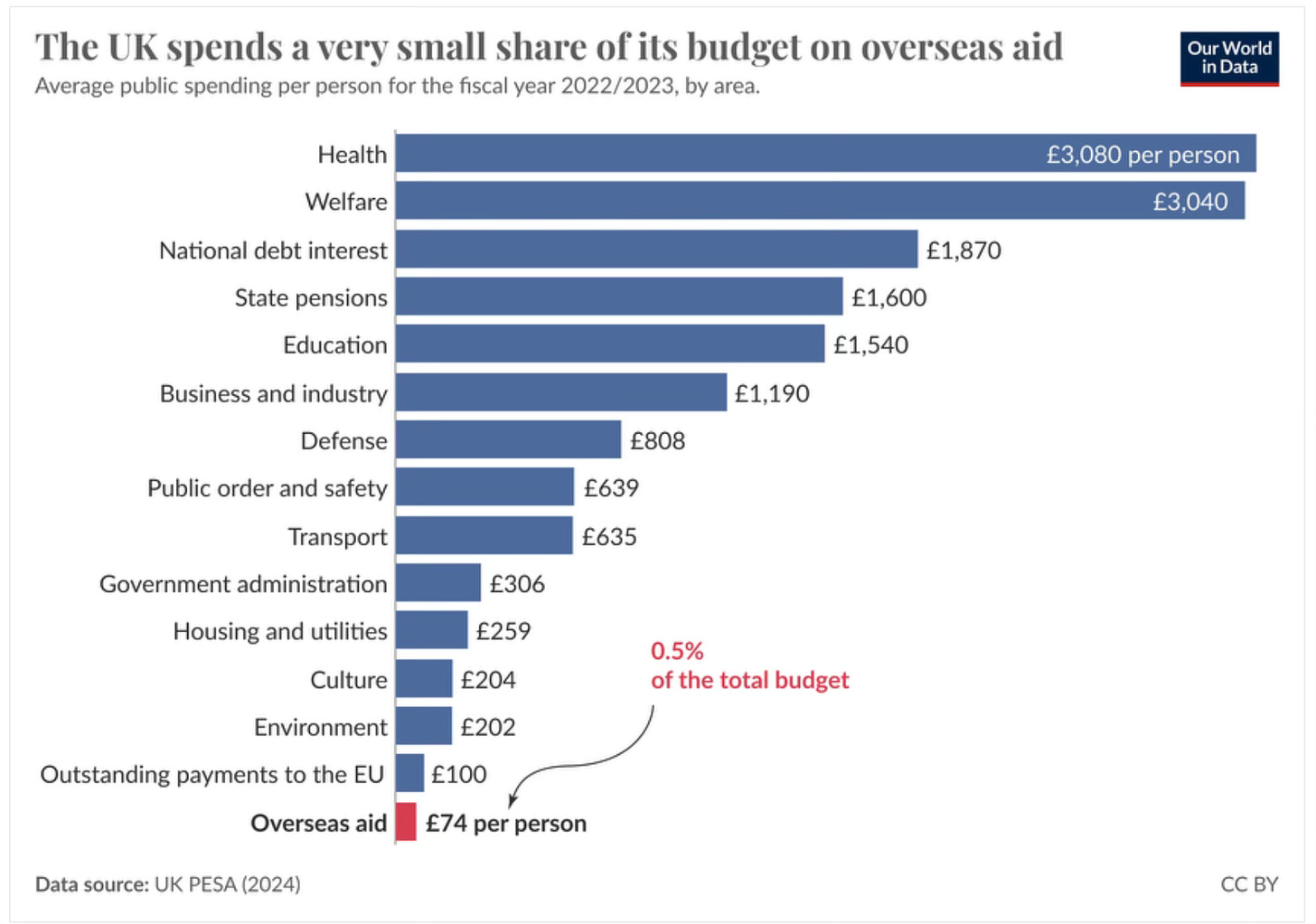

Except by the British people. Like so much else, populism ruins the ability of many to see what should be obvious to all. On the issue of actual spend on overseas aid, juxtaposed with other public sector expenditures in Britain, the perception of the British people is just plain wrong. Here is the data, compiled very helpfully as usual, by Bastain Herre over at Our World in Data.

As with all things in this day and age—the actual facts will not swing voters to change their minds. UK aid is stuck dealing with a problem it didn’t create. And the price will be paid by those that benefit (or could benefit) from the vast and incomparable influence that FCDO nee DFID had (and have).

One small example of how these kinds of debates end up shaping outcomes is the reported delay of UK’s over 700 million British pounds strong contribution this year to IDA 20—IDA being the financial mechanism through which UK taxpayers contribute to the overall health of the World Bank’s ability to issue grants and concessional loans to developing countries. Both multilateral and bilateral FCDO contributions to a wide array of sectors, such as public health, tend to be crucial for many countries—and the growing ODA-skepticism in the UK will hurt all of them.

ODA is Stage IV. It will continue to fall

The bad news is that this is not going to get better soon. It can’t. The political “moment”, across the spectrum of OECD, is one of unrelenting partisanship, and often, cruelty. Domestically, citizens in the West don’t want migrants landing at their shores. Globally, they don’t want their tax dollars being spent hundreds (often thousands) of miles away. The press doesn’t ever report on the billions of productive and impactful transactions that take place due to the global development (or ODA) architecture—but they report robustly on every scandal. Each scandal becomes the whole story. Exploitative algorithms on social media, and exploitative populists in politics take advantage of these opportunities. Globalization, even though it isn’t going away, now has a stink. ODA is one of the easiest and most convenient hooks upon which to hang the stink.

Ukraine is the singular exception—and here too, there are plenty of small, but growing enclaves of dissenting opinion in the West. Aid for Ukraine grew against the trends visible everywhere else. But neither military assistance for Ukraine, nor post conflict rehabilitation and reconstruction are guaranteed to find enthusiastic support in most Western public discourse. The exceptional status DFID and now FCDO have enjoyed will endure—but the trajectory for this influence will flag as the funding mechanisms begin to lag behind both the needs of highly indebted, climate vulnerable countries—many of whom find warmer and smoother conversations on financial support when they land in Beijing, or Abu Dhabi, or Doha. Times are changing. Overseas development assistance should too.